Despite the economic crisis that plagued Italy during the seventeenth century, art remained a staple of Church investments. Designed for a much more educative role and opened to a wider audience, seventeenth-century art make emotion and engagement as its two key terms. Obviously, the authors – besides their passion – painted for profit, sometimes sharing the same square and trying to get the most prestigious commissions and the most profitable jobs. As contemporary big brands, the artists of that time shared a market made up of demand and offer, and the parallelism, although little dary, allows us to understand the mechanism for which names like Caravaggio, Reni, Vermeer, Rembrandt, Zurbarán, Artemisia Gentileschi and others are known to everyone in the landscape of art lovers and scholars and why other minor (and for various reasons) are not.

By delimiting the discourse to Rome alone, for example, apart from the already mentioned very famous Caravaggio and Guido Reni, several other artists were busy doing frescoes and decorations. Yet, about an artist such as Vespasiano Strada, author of today’s work, we have come to believe that he had disappeared during the pontificate of Sisto V; fortunately, in addition to his accomplishments, there is also a document about a fee of 12 scudi dated October 22, 1609. The Strada is just one of the many names that populate the limited and vibrant Roman panorama: Francesco Vanni, Andrea Lilio, Giovanni Zanna and Vespasiano Strada were the protagonists of this seventeenth-century market of professional painters of whom today we know scudi and art.

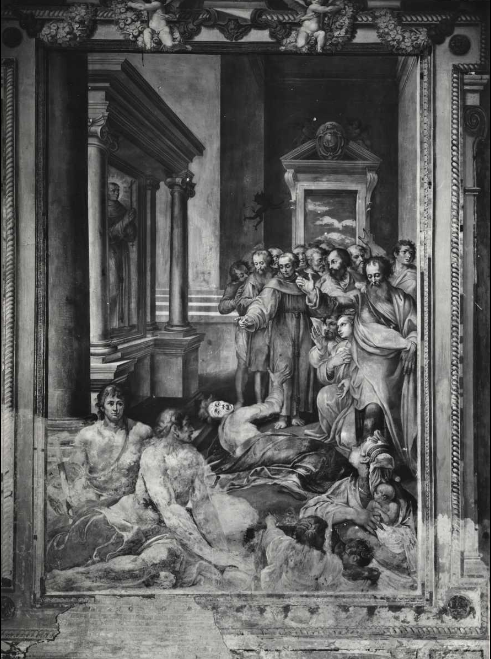

This seventeenth-century art market was the result of a profound socio-cultural change, where, following the crisis that affected the church, religious sentiment gained an increasingly important role, and it is precisely about this cultural climate that today’s work speaks to us, representing its reflection. Even though it is not considered a masterpiece, or perhaps just for that, Vespasian’s painting exalts the main feature of Baroque art which is spirituality. “Nothing can be better than the image to raise our feelings, nor wake something so subtle in our soul,” wrote Cardinal Paleotti in his Discourse about sacred and profane images. According to him, the main function of a visual representation would be to convey the message, which, having a stronger communication power, shows itself as superior to the verbal one. So we come to the idea of compassio, that is, a kind of empathy that the observer should feel in front of a religious painting.

That awakening of religious sentiments became such an indispensable requirement that defined the whole concept of baroque art, but not only. The church’s need to express and recover its power leaves us an art dictated by its absolutism and, as a result, is interpreted as the first appearance of art for the masses, the first attempt to create a mass culture that, of course , is gravitating around the Catholic Church. Here, for the first time, we can talk about media propaganda, where art becomes a propagation means of ecclesiastical mechanism, which required many painters in order to awaken a kind of admiration and bring observers to true faith. Some of them moved the boundaries and elevated baroque art to a higher level, while others, as the author of today’s work, open up new horizons to complete the frame of the seventeenth century.

Representation of a Spanish saint, San Diego of Alcalà, opens up many new themes and shows us the complexity hidden in the study of so-called minor artists. Not only the importance of iconography as a means of conveying the message to the faithful, not just the details related to the client and the chapel where the painting is, but the story of the saint itself becomes the starting point for various interpretations. Revealing the link between the Catholic Church and its new ally, Spain, highlights not only the importance of the historical context but also of the religious orders for baroque art. From here, links could take us in different directions, but they will be part of another article…

Vespasiano Strada

San Didacus of Alcalá heals an obsessed men

1610-1615

Fresco

Rome, Church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, right nave, seventh chapel, side wall