It is November 26, 1903, and a famous and disrispectful Gustav Klimt writes to the ministry requesting that some of his works be exhibited in the Magna Hall of the University of Vienna. Shortly thereafter, in December of the same year, the Viennese secession newspaper, the Ver Sacrum, blocked the rotators forever. In the years between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, in an atmosphere of fervid popular participation and cultural elite around the themes of the res publica, the Austrian artist is entrusted by the Ministry of Culture and Education to decorate the most important environment of the Alma Mater Rudolphina. In doing so, starting his work in 1898, Klimt intends to represent anthropomorphization of the three faculties characterizing the Viennese university: Philosophy, Medicine and Law.

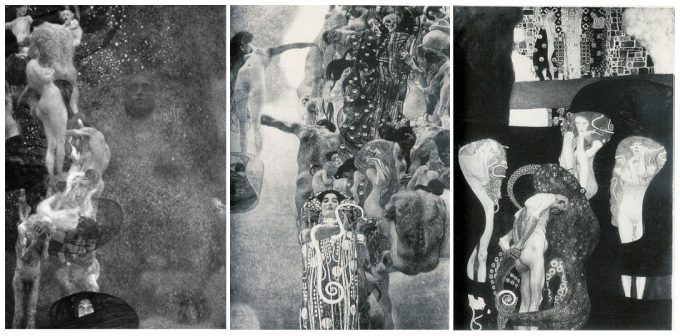

The story we tell today is crucial for understanding the artist’s relationship with the state commissions and the spirit that moved his brush. As a supporter of public art, Klimt saw in it the only way to free the work from its mercification and, therefore, to combine it into an elitist paradigm where architecture was integrated with painting. For these reasons, it is easy to assume the disappointment he must have experienced when, in 1900, at the presentation of the first of three works during the 7th Exhibition of the Secession; Philosophie, in fact, received numerous criticisms. To show such disdain were the same university professors who – in a large number (we are talking about almost 90 professors) – decided to protest against this accomplishment headed by the Rector himself. To provoke this indignation was the allegorical proposition set in the intentions of the artist. In the panel, a group of female and male bodies wrapped together, like in trance, would have to, according to Klimt, represent birth, fertility and death. As an enigmatic universe emerging from the mists of unconsciousness, a globe of earth appears to the right of the bodies with the semblance of a human face: beyond the vicissitudes of men and their life cycle, the dark mystery remains unmistakable and, the only shattering of darkness can come from wisdom alone, a figure of pure light that – emerging from below – illuminates the bodies of men. Traditional formal representations for the Viennese audience are less and a tidal wave of symbolic limbs convey the despair or serenity that characterizes the common human; not the genius of the past to be celebrated, but the very meaning of the wisdom that throws light where darkness is thicker and where Philosophie was shoved for the first time. This vision was not appreciated, however, by the academic audience who saw in those covers only a mass of meat sensually represented, as in a damned orgy: the Klimtinian group of the lustful. Yet there is something else in Klimt’s work, something he tries to carry out despite protests, insults, and letters of remorse brought to the attention of the Ministry of Culture and Education, letters that suggested a review of the committee set up in 1894 for the artist. He did not give up. In 1901, Medicine, pregnant, is suspended between skeletons and nude bodies, once again for its detractors, between anatomy and pure sensual and orgy-like delirium. This time, the work did not only recorded a huge number of curious visitors (nearly forty thousand) but also prepared the ground for the definitive ruin of the triptych. Two years later, in 1903, Jurisprudence was presented and it is the drop that overflows the vase: even a parliamentary question is set up, that aims to declare the works unsuitable for display in the Great Hall of the University. The outcome of this proposal was positive. The works were therefore moved to the Modern Art Gallery built in those years.

Klimt’s regret was such that he wrote with his own hand at Minister Von Hartel to relocate the panels where they would have to remain. Unfortunately, he did not have the good fortune and – as already said – this affair caused the material ruin itself of the decorations. Two years later, Klimt explained to a friend Berta Zuckerkandl that the reason for his displeasure was not the result of criticism as to the disappointment of losing consideration to a public contractor: “I gave up the job that was entrusted to me by the Ministry of Education, not because I felt offended by the many attacks that had been made against me. I’m insensitive to those attacks. The Ministry made me understand that I am embarrassment. For an artist there is nothing more painful than creating works, receiving a reward, for a buyer who does not fully support him with the heart and the reason. “

Klimt continued his career as an illuminated and affirmed artist under several patrons, and in 1907, he was even able to buy his decorative triptych and to rework it completely.

The story could have ended here but unfortunately this is a story without a happy ending. After the death of the artist in 1918, two industrialists bought the three fakultätsbilder which were subsequently requisitioned by the Nazis in 1938. After a celebratory exhibition in which they were exposed in 1943, the paintings were shipped to the famous castle of Immendorf, which became a kind of artwork warehouse that included most of the artist’s collection which was more than a large part of the private collection of industrial Lederer.

Unfortunately, Immendorf was the last dwelling of those works: in 1945, the SS, despite not leaving in the hands of the Russian troops the castle and the preserved works of art, started a fire burning thus all that was in its interior. Of Philosophie, Medicine and Law, there are only black and white photos, a reminder for those who look at them, and a cause of great regret.

In the movie The Monuments Men, the capable and courageous director of George Clooney, rewrite Robert Morse Edsel’s book on film, which deals with a group of intrepids who do everything to save works of art from the Nazi ruin and allow future generations to be able to enjoy at the cost of living. And even if we would like to be able to remain in the field of fiction or at least in the past, our thought can only address the recent destruction of the Assyrian cities of Nimrud and Hatra, Mosul, Raqqa and Palmira, ancient innocent witnesses of a bloody folly that has been pursuing the human being forever and seems to be able to sweep away even those monuments which they are capable of accomplishing.

For us and the posterity there is only a memory that remains and we have the obligation to always make the best possible use of it.